Why You Should Forget All About Sustainability

Until last year, I was Cuningham’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Not anymore. Now, I am the firm’s Director of Regenerative Design — a title shift that mirrors the necessary steps we all must begin to take in our professional and personal lives. I am, of course, talking about the industry-wide need to shift away from “sustainability” and into regeneration.

Wait… what’s wrong with sustainability?

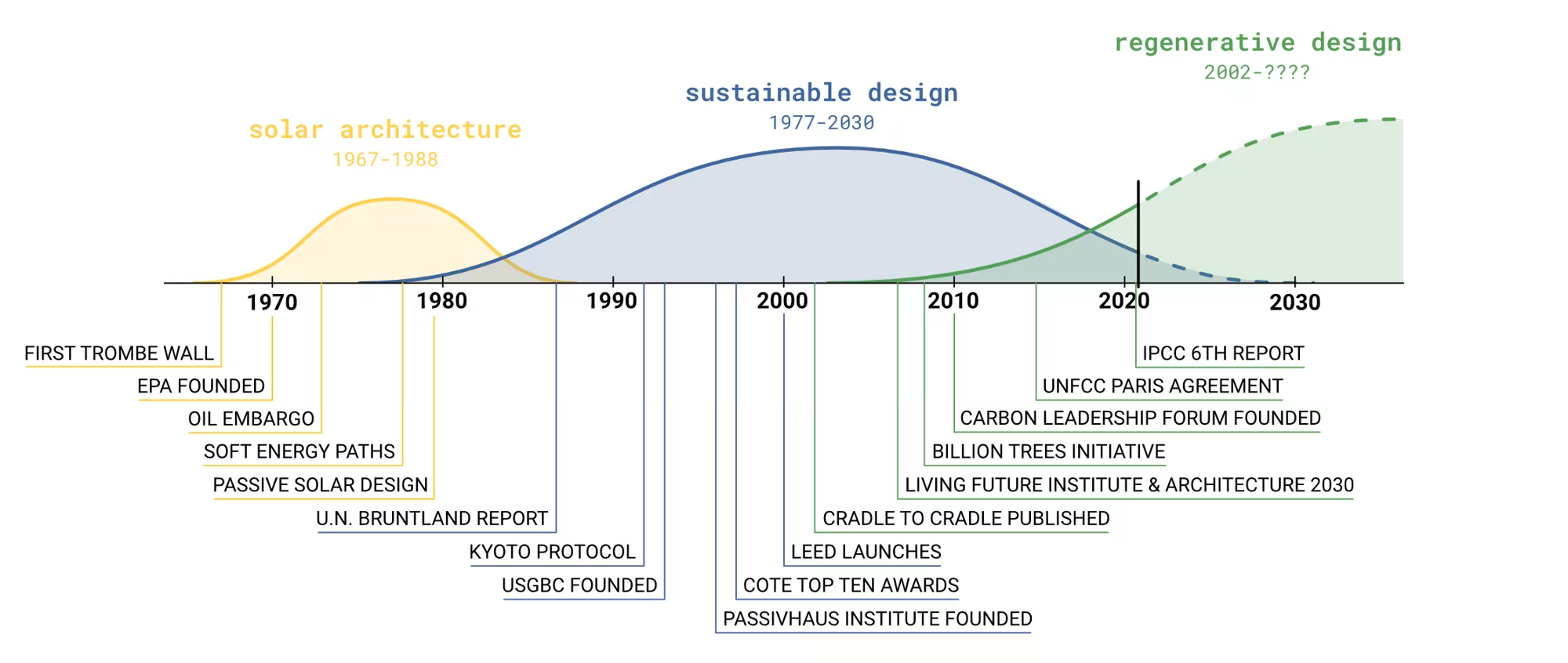

As a practicing architect since the late 1970s, I have observed the evolution of environmentally-conscious design and believe there have been three distinct, yet overlapping, movements. I think of them as waves with one coming in as the previous one recedes.

When I began working as an architect, we didn’t even use the term sustainability. We called this approach “Solar Architecture.” The founding of the EPA in 1970 and the oil embargo of 1973 were two major events of the short-lived era. By 1988, designers had largely forgotten it. “Sustainable Design” was the new zeitgeist. Sustainability has lasted much longer than Solar Architecture. Highlights of the Sustainable Design movement were the founding of the United States Green Building Council (USGBC) in 1993 and the first version of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) in 2000. Today, the concept of Sustainability Design is falling out of favor and “Regeneration” is its replacement.

Looking back at Solar Architecture, the central concern was that we were running out of fossil fuel, especially natural gas. We had little concern for electricity use and we ignored peak load. Instead, we focused on heating and cooling strategies (which often resulted in over-heating) and made extensive use of daylighting. It was a very narrow focus, but a necessary precursor to sustainability.

During the 1980s, Sustainable Design got started and by the middle of the 1990s it was an important movement. The paradigm that drove sustainability was “Do Less Harm.” The interest in this model peaked a few years ago and is already declining.

Thousands of buildings across the world were constructed to be sustainable. These buildings all have one thing in common – they do less harm, but still use energy and water, and create waste. Our design for Aspen Middle School from 2006 is a good example. It avoided nearly half a million pounds of operational carbon emitted every year. Unfortunately, most sustainable buildings created more embodied carbon in order to reduce operational energy.

A necessary next step

Sustainability has undeniably achieved a lot of good, especially in terms of energy efficiency. According to Architecture 2030, even as the area of buildings in the U.S. has increased greatly, the energy used by those buildings has actually decreased. We succeeded in decoupling floor area and energy use.

Unfortunately, sustainability is worn out and designers and clients are losing interest. LEED registration is a very good indication of interest, and in recent years we have seen what can only be described as LEED Fatigue — a decline from 8,425 new certifications in 2015-16 to 1,472 in 2018-19.

Beyond the building sector, the news is much worse. Our planet is in real trouble! During the era of Sustainable Design, measures of environmental health such as biodiversity, plastic pollution, deforestation, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and food and water insecurity have gotten much worse. Many of these relate directly to how we plan and build. We need a different approach. It’s time for something new.

That brings us to regeneration. As we recognize that sustainability no longer excites our clients and ourselves as designers, regeneration is where we must go. We want to design projects that actually do good and repair the damage that has occurred. Whereas sustainability meant “Do Less Harm,” the paradigm for Regeneration is “Restore the Planet.”

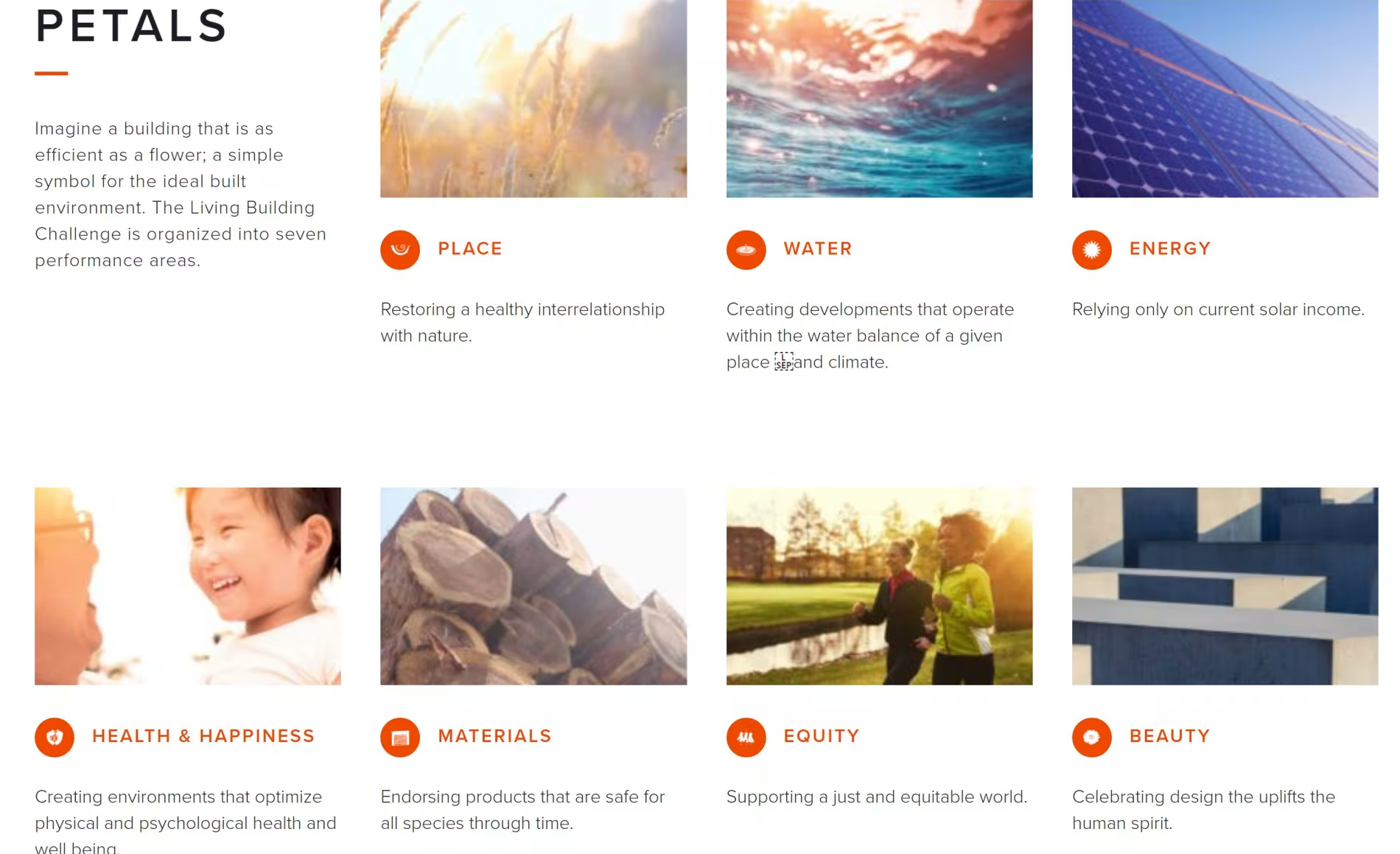

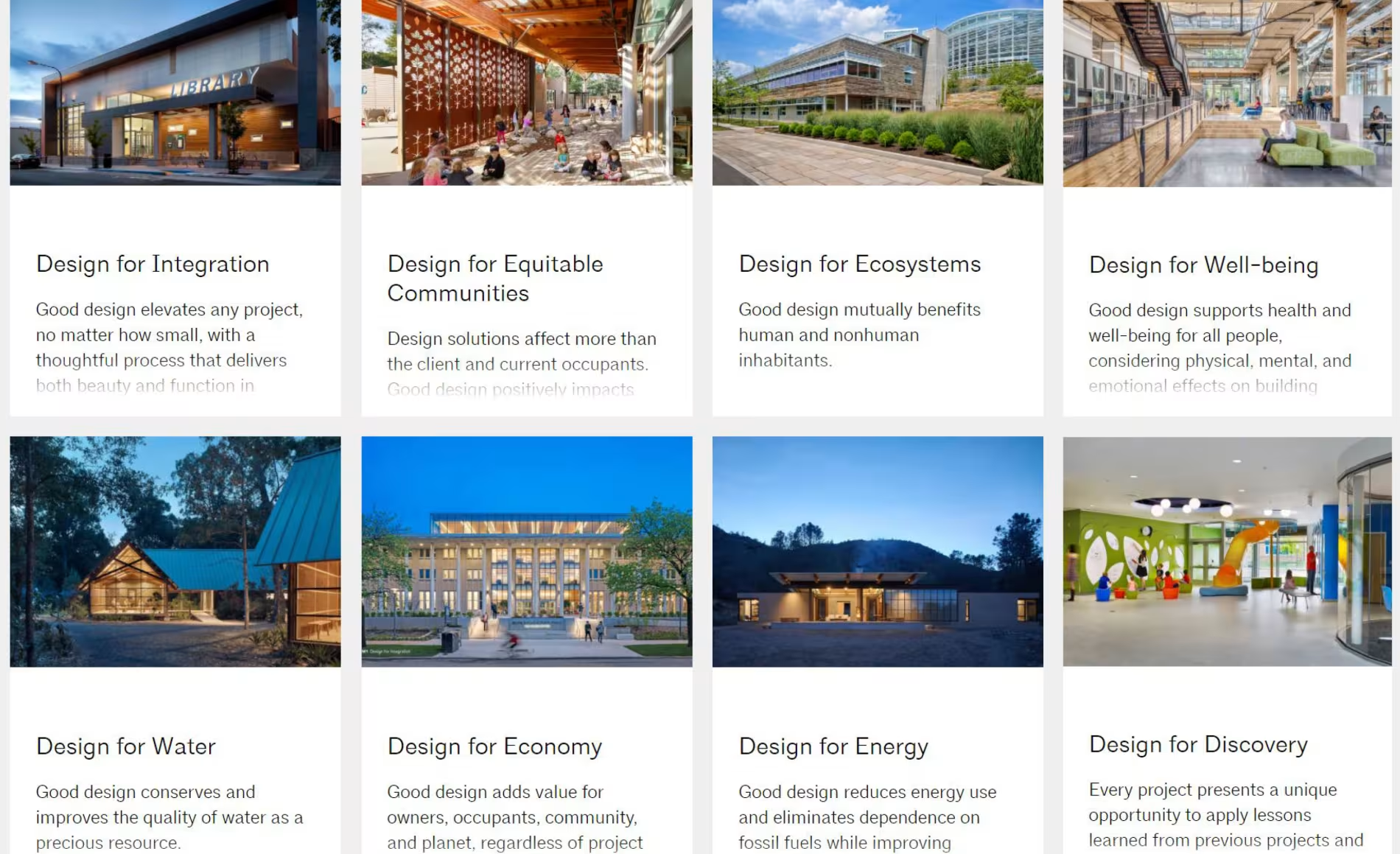

The Living Future Institute has already done much to promote Regeneration. Their seven petals are a great place to start working on Regeneration. The American Institute of Architects has also recognized the importance of Regeneration. Their new Framework for Design Excellence has ten categories. Notice, the word sustainability is nowhere in this list.

Regeneration strategies at Cuningham

I’d like to share the regenerative strategies we are implementing at Cuningham. The first is to set an example with our own operations. We can’t ask our clients to do what we aren’t. So, we monitor our carbon emissions and reduce or offset them. We are developing a Climate Action Plan, and we have worked on Justice Equity and Diversity at our company.

Next is to work with existing buildings and infrastructure, rather than demolishing them. Our firm has always done this type of work and it is increasing. I think in the future, designing an all new building will be rare and most of our work will be renovating or adapting existing. Our office in Phoenix used to be a bank building.

Whether building new or renovating, Regenerative Design must include energy and pursuing Net Zero. We can’t deal with climate change unless all our buildings pursue this goal. At Sierra Grande School in Colorado, we are doing just that. It is on the path to Net Zero Energy even though it is in a very cold climate. In addition to Net Zero Water, we also strive for One Water. Where I live in the American west, that is extremely difficult as we have very little rain. Yet buildings such as the new Denver Water Board Building by Stantec are getting it done.

We are also trying to stop generating so much waste, both during construction and after completion. At North Park School for Innovation in Minnesota we are getting close to Net Zero waste. A biodigester is one key strategy in this effort. We can also stop generating so much carbon with the materials we use; our work on Aspen Community School focused on reducing embodied carbon through substituting wood for steel structure.

The last strategy is habitat restoration and preservation. For me, this hits close to home — literally! I am fortunate to live on a ranch outside Denver. My wife and I designed it to restore the land to its condition before 100 years of ranching and cattle damaged the ecosystem. After 20 years, we are beginning to succeed. Vegetation is rebounding and animal species are returning. The image below show the difference in vegetation over the last 15 years.

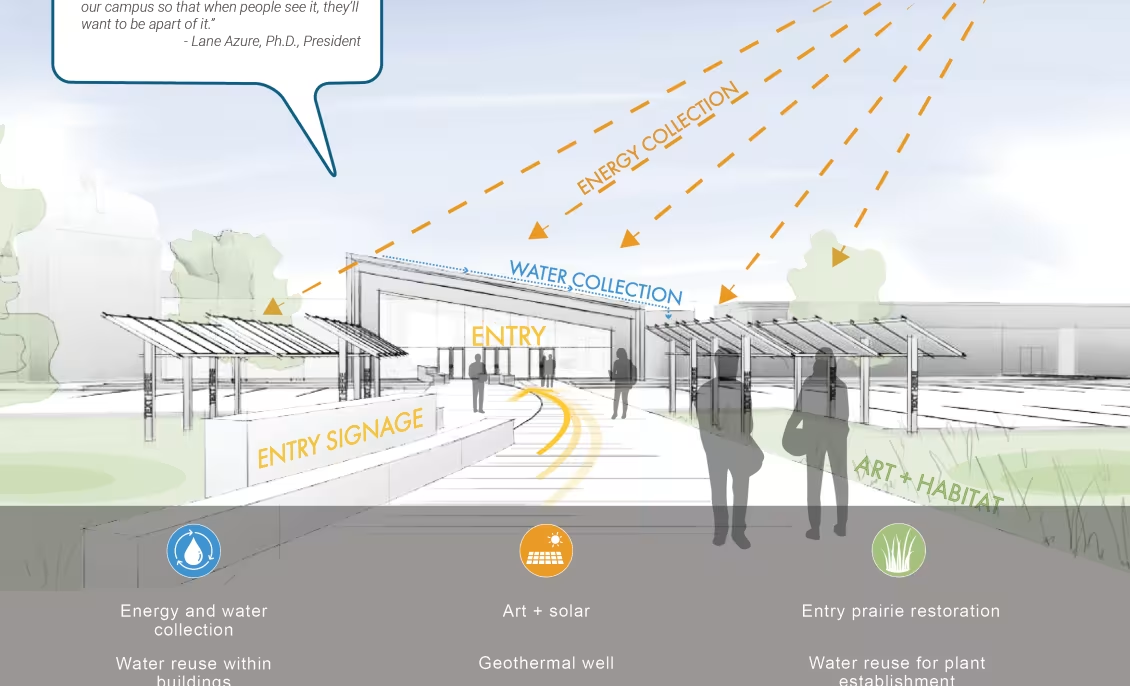

Can all of these strategies be brought together in one project? Cuningham thinks so. Our regenerative master plan for Sisseton Wahpeton College, a Native American college in South Dakota includes a path to reusing all existing buildings, net zero energy, net zero water, habitat/prairie restoration, and waste strategies. We expect to be doing more of this kind of work.

Regeneration moving forward

We see many proposed projects that claim to be regenerative in the news. Typical features are all horizontal surfaces covered in vegetation, underground utilities and HVAC systems, and integrated solar panels for energy production. If these projects and cities were built, would they be regenerative? Would they do more good than harm? Do they result in a healthier planet? We don’t know the answers to these questions yet, and we should ask their designers to provide the answers.

In the last several days, I have heard regeneration mentioned in unexpected places. I saw an ad saying that Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, is becoming regenerative. Then, a few mornings later, I heard the chairman of the USGBC state that Regenerative Design is our future.

At Cuningham, we recently re-thought our Mission, Vision, and Values and they are informed by our desire to become regenerative. We acknowledge that we are not yet creating Regenerative Design, but we are doing much less harm than before. It will take more time for us to learn how to design in a way that truly restores the Earth, but we have committed to this path. I am convinced we will successfully move from sustainability to regeneration, just as we did from Solar Architecture to sustainability 30 years ago.