Through the Lens of Trauma-Informed Design

Trauma-informed design is an approach to the built environment that is rooted in equity and empathy. As the concept rapidly gains traction in the design industry and beyond, Cuningham is working to show how educational environments can incorporate trauma-informed design concepts into a project’s vision, goals, and design process.

Understanding Trauma

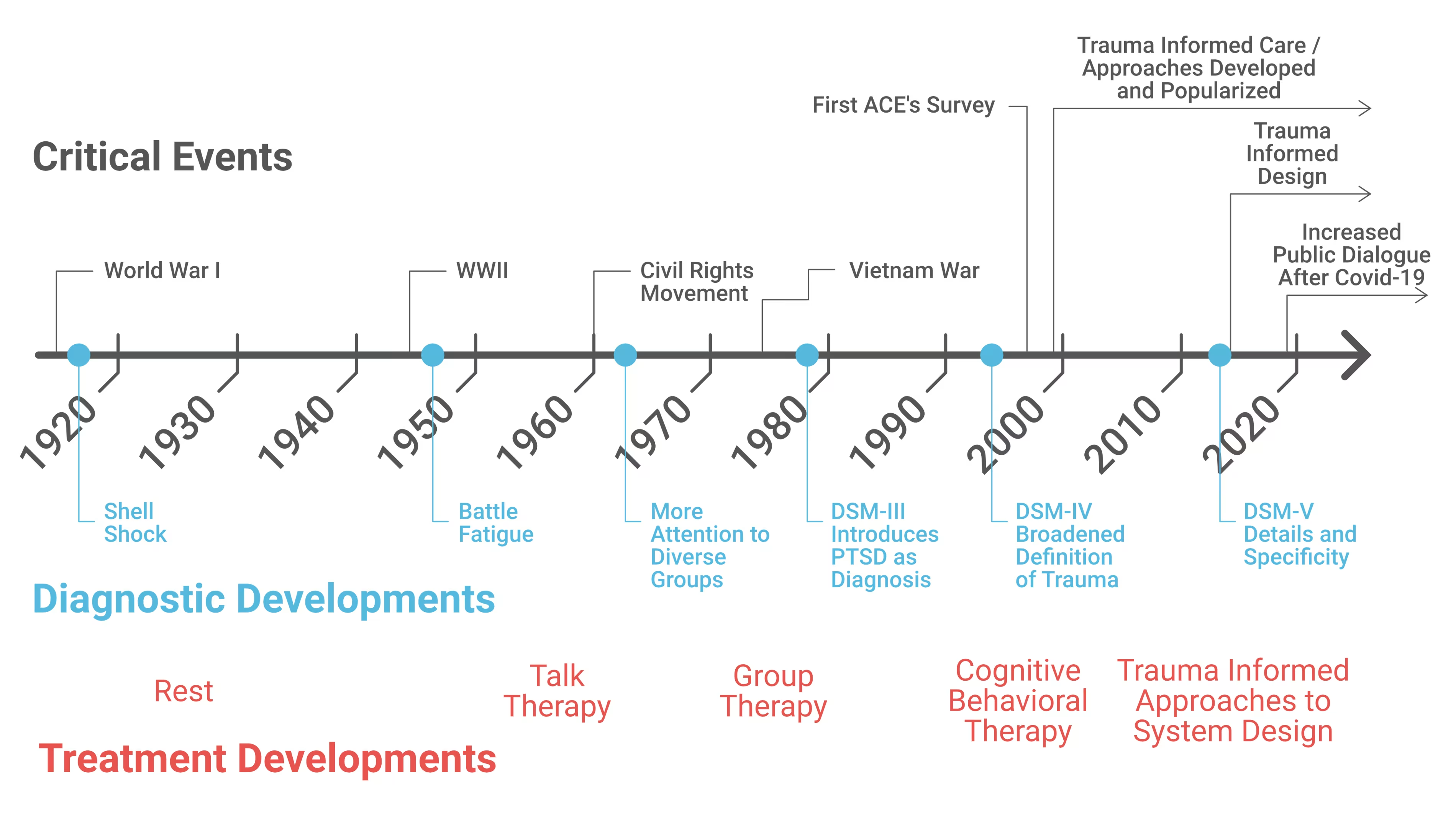

Our understanding of the concept of trauma has changed greatly over the past century. From believing the stigmatized [1] effects of shellshock (what we would now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) experienced by WWI veterans was physiologically related to shockwaves, to recognizing during the social movements of the 1960s that individuals could suffer long-term, psychological impacts from violence outside the scope of war, we’ve come a long way in understanding trauma.

The medical terminology around trauma became formalized after the Vietnam War when “PTSD” was added to the DSM-III and extensive research began on the newly defined condition. [1] Three decades later, the DSM-IV broadened the definition of a traumatic event, which gained specificity in the current DSM-V.

An influential 1998 study has since become a foundational reference point in the development of trauma-informed approaches. This study, commonly known as the “Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Survey,” [2] was conducted through a partnership between Kaiser Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [3]. The study sought to answer a simple but incredibly important question: do individuals who experience trauma during early childhood have lasting negative outcomes later in life?

The survey, which collected data on past experiences and possible risk factors from over 9,500 respondents, found a statistically relevant link between traumatic childhood experiences and risky behaviors in adulthood. It even found links between these experiences and chronic health conditions associated with early death.

Some noteworthy findings from work done in subsequent years indicate that substance abuse challenges, mental health disturbances, risky sexual behavior, somatic health challenges, memory and retention, job performance and academic performance can all be impacted by these adverse childhood experiences (ACE) [4] [5] [6] [7]. The CDC provides an online clearing house for those who would like to know more about these studies [3].

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), an organization that provides services for individuals with mental and behavioral health challenges, recognized early on the importance of the ACE studies and incorporated their findings into the organization’s work. In the years since, SAMSHA has established themselves as one of the foremost authorities on “trauma-informed approaches” to healthcare delivery and public service programming. Their definition of “trauma informed” is the one of the most likely to be quoted and referenced in the field. It is as follows:

“[Trauma is a] result of an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.” [8]

Making an Impact Through Design

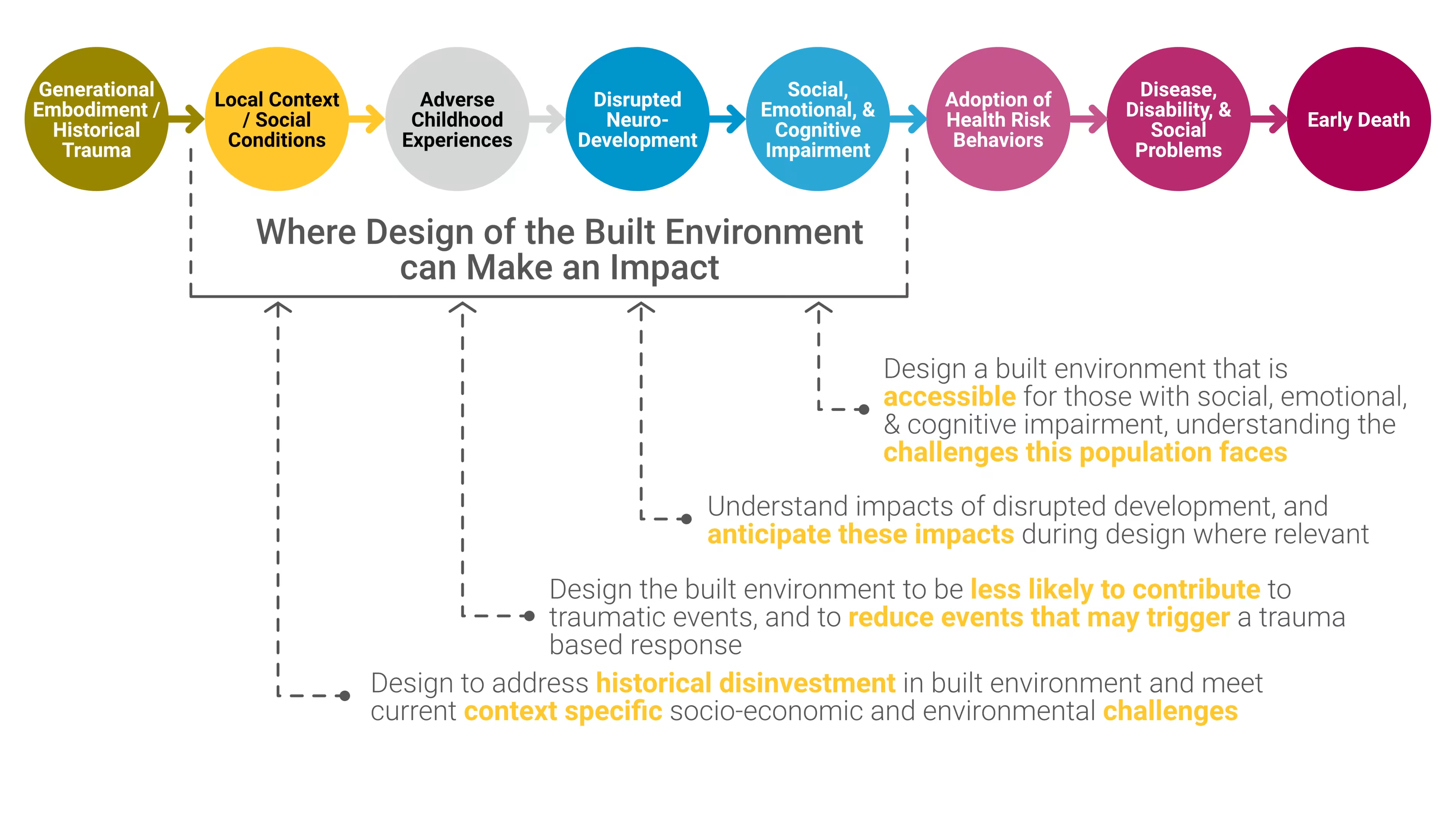

We believe the built environment can — and should – play a significant role in alleviating and reducing trauma. While the cycle of impacts surrounding an adverse childhood experience can be disheartening, it also presents a roadmap that details design’s powerful ability to intervene in the following ways:

- Local Context / Social Conditions: Design can address historical disinvestment in underserved communities and meet context-specific socio-economic and environmental challenges

- Adverse Childhood Experiences: Design can create spaces that are less likely to contribute to traumatic events and reduce events that may trigger a trauma-based response

- Disrupted Neurological Development: Design can accommodate impacts of disrupted development on an individual’s perspective and behavior

- Social, Emotional and Cognitive Impairment: Design can create spaces that are accessible for those with social, emotional, and cognitive impairments, and avoid exacerbating conditions

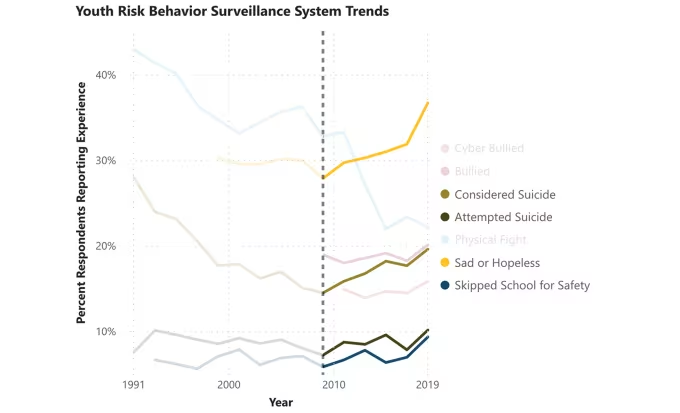

Educational environments have a distinct challenge to address with trauma-informed design as young people today are facing unique mental health challenges. According to the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [9], in the past decade students have increasingly reported being impaired by feelings of sadness or hopelessness — there has also been an increase in attempted suicides and students who have skipped school because they felt unsafe.

We must recognize that schools are not neutral environments [6]. They are sometimes sites where traumatic events in a child’s life can take place. Schools can reinforce and remind students of class and socio-economic divisions. They are places where students may encounter bullying and discrimination from peers or teachers based on race, gender, or other identity factors. There are also educational factors such as test-taking and receiving grades that are inherently stressful.

While the buildings alone cannot solve these societal scale challenges, trauma-informed design offers a lens through which school design can create positive outcomes and reduce harm for their occupants and their communities.

What Constitutes Trauma-Informed Design?

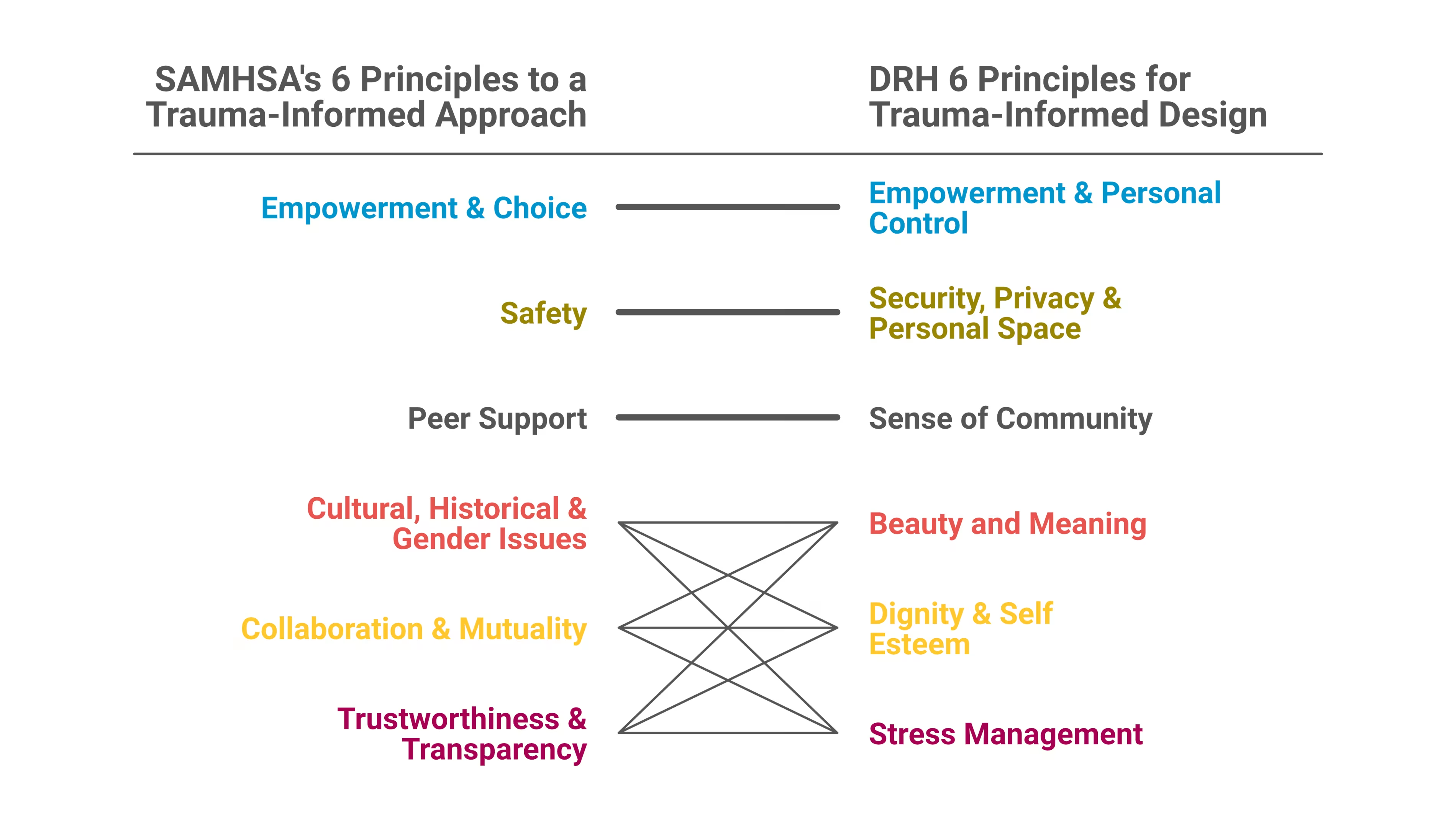

The precursor to trauma-informed design was trauma-informed care, which focused on how services are provided to vulnerable populations in a healthcare setting. In 2014, SAMHSA [8] used their experience researching and implementing care-based approaches to develop six, generalized principles for trauma-informed approaches to programming beyond medical spaces.

- Empowerment & choice

- Safety

- Peer support

- Cultural, historical, & gender issues

- Collaboration & mutuality

- Trustworthiness & transparency

Soon after, Florida-based non-profit Design Resources for Homeless (DRH) [11] published a guide for the architectural implementation of trauma-informed design which included its own set of six principles, framed specifically in the context of the built environment. This thoroughly-researched report is one of the earliest resources to apply trauma-informed concepts to architectural design. While DRH’s principles were not explicitly based on the six principles outlined by SAMHSA, their similarities are clear.

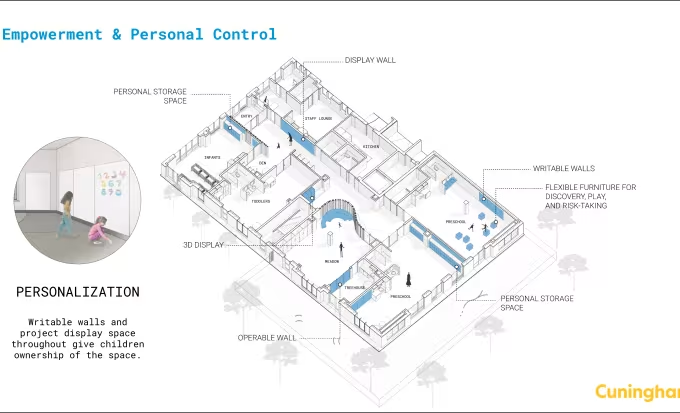

- Empowerment and Personal Control

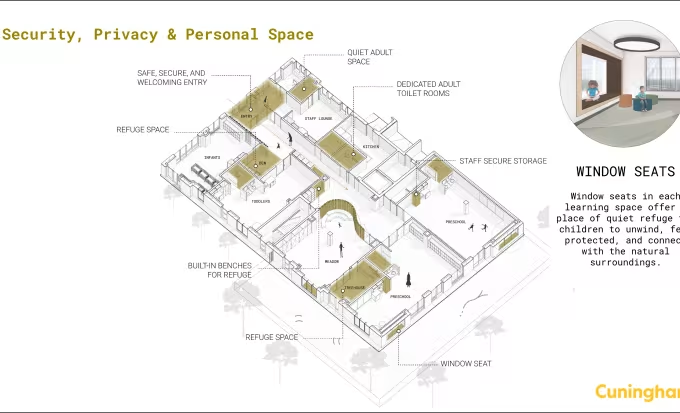

- Security, Privacy and Personal Space

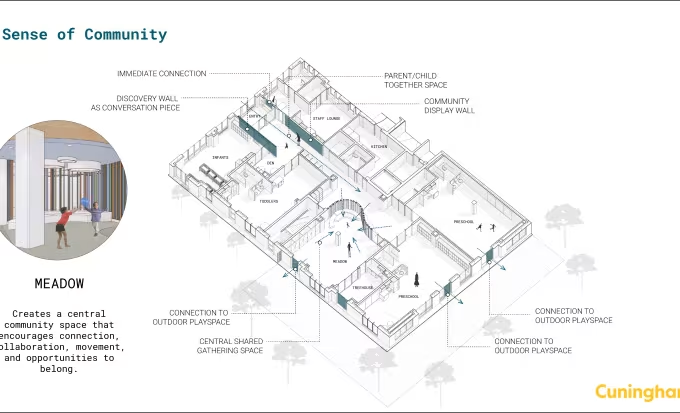

- Sense of Community

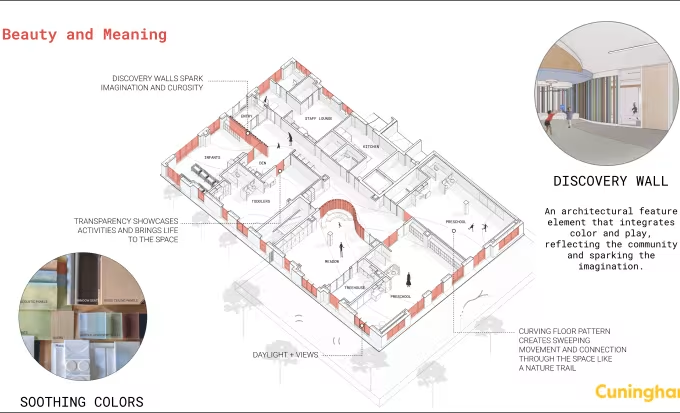

- Beauty and Meaning

- Dignity and Self Esteem

- Stress Management

While several authors since DRH have proposed various taxonomies for considering trauma in design, we believe DRH’s principles have several unique advantages that help designers and their clients understand the subject matter: they build on SAMHSA’s established authority regarding trauma-informed approaches; their universal nature allows them to be broadly applied to nearly any building type; they were established by a non-profit with ties to a university.

To help us understand how these principles apply to design, we created generalized definitions of these principles based on the context available in the original DRH report [11], academic literature referencing this report and dialogue regarding how these principles may apply to educational environments.

Empowerment and Personal Control

Design strategies that give occupants a sense of agency through the ability to adjust the built environment. By allowing users to shape their own experience in a space, self-expression is encouraged.

Within a school, this might mean pinup space for personalization, mirrors in play and recreation areas, choice between variety of furniture types, operable windows & shades, space for growing plants and hands-on activities, and writable surfaces.

Security, Privacy and Personal Space

Design strategies that help occupants feel safe by providing options to enhance their privacy while also being spacious enough that everyone can have adequate personal space.

Within a school, this might mean prioritizing clear wayfinding, sightlines and boundaries, minimizing negative triggers, offering vantages of both prospect and refuge and paths of retreat, and recognizing the role of teachers and specialists in shaping a sense of safety; and providing distinct spaces to enhance the sense of safety for staff members.

Sense of Community

Design strategies that help occupants to create community by providing spaces to meet and gather around specific tasks, events, programming, or times of day, in a contextually appropriate manner.

Within a school, this might mean multi-level gathering spaces, living room style furniture, using furniture to subdivide large spaces, ties to neighborhood and community contexts, conversation pieces, tailored community spaces, and community resources.

Beauty and Meaning

Design strategies that help to create spaces that reflect the cultures and identities of the occupants. The finishes will highlight natural, authentic and comfortable materials, and create spaces that are inspiring and impactful on their occupants.

Within a school, this might mean culturally relevant designs, a preference for natural or soft furniture or flooring materials, reducing clutter by providing adequate storage, carefully considered color schemes, and embracing natural amenities with nature walks, learning trails, and courtyards.

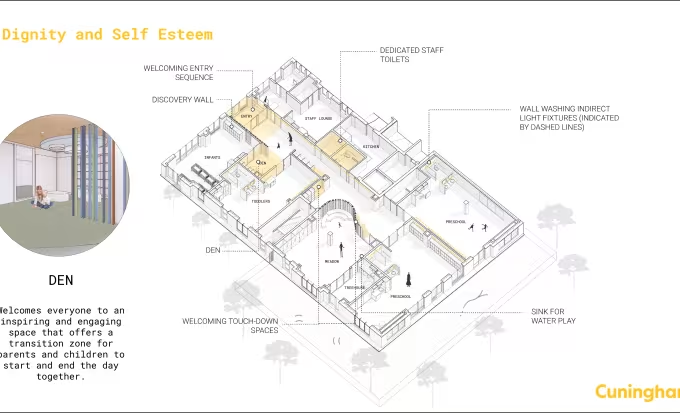

Dignity and Self Esteem

Design strategies that help foster and celebrate each occupant’s inherent worth as an individual, communicate positive messages about their value, and provide ways for them to express and emphasize their strengths and potential.

Within a school, this might mean a welcoming entry sequence, thoughtful and well-designed storage for students’ personal items, furniture and fixtures sized to occupant ages, use of side lighting near mirrors to provide more flattering lighting, and providing amenities to staff that enhance their performance and recognize the importance of what they do.

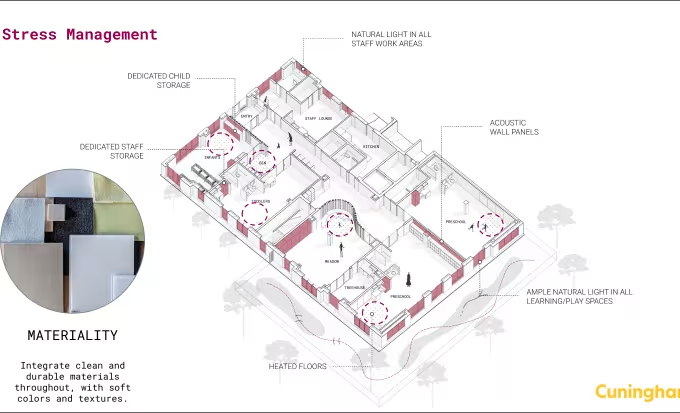

Stress Management

Design strategies that help create spaces which are comfortable, clean, quiet, and calming. These strategies can be used to provide areas for individuals who experience high amounts of stress to self-sooth and manage their experience.

Within a school, this might mean providing plentiful natural lighting, selecting finishes for ease of cleaning, providing appropriate amounts of acoustic mitigation, interior lighting for circadian rhythms, integrating seating into windows, using cool or calming colors, and soft forms.

Rise Early Learning: Assessing an early childhood project through the lens of trauma-informed design

Rise Early Learning is a new early childhood education facility in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. A first-of-its-kind project for the state of Minnesota, Rise Early Learning is a tenant within an affordable housing community, funded by Common Bond Communities and designed by Kaas Wilson Architects.

Cuningham was brought on by the client to develop an early childhood education space that adhered to the project’s existing three guiding design principles: trauma-informed design, equity, and play. Together, we developed the project vision statement below.

Rise Early Learning Center welcomes all families and teachers to a nurturing, equitable, and fun space. Curiosity and exploration are unbounded as the space is flexible and adaptable to support open-ended play and creativity. Natural, textural, and clean materials provide a backdrop for children's activities, projects, and artwork to shine.

By engaging Rise Early Learning’s community members and future occupants in co-creative workshops that explored a range of strategies for supporting children, parents, and staff both physically and mentally, Cuningham developed a “Heart of Play” concept for the project. This approach locates an informal play area in the center of the space, giving equitable access to all the surrounding learning spaces while also being connected to the outdoor areas. You can see many of these ideas detailed in the diagram below.

As our first project incorporating trauma-informed design into the design process, we familiarized ourselves with these concepts as they related to the project’s Concept / Schematic Design phase. As the project progressed, it was clear that these concepts had a valuable role to play not just on projects where the client is asking for them specifically, but on all educational design work.

After a thorough literature review, which formed the basis of the beginning of this article, we self-assessed our design on Rise Early Learning by how well we created a space that met our (now) much more robust understanding of what it means for a space to be “trauma informed.” To conduct this self-assessment, we created an archive of every related design strategy we could identify. We searched for strategies in our own past and present project work, in the literature about trauma-informed design, and in broader literature around designing for wellbeing, mental health and happiness [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17]. By assessing Rise Early Leaning through the lens of trauma-informed design, the design team was also able to identify opportunities for growth during future design phases.

Empowerment & Personal Control

Rise Early Learning makes use of design strategies that support the principle of “Empowerment & Personal Control” by giving occupants the ability to personalize their space and their experiences. Display walls provide space for pinning up work for all to view and appreciate, and writable walls give students ways to express themselves while learning.

Security, Privacy & Personal Space

Design strategies that support the principle of “Security, Privacy & Personal Space” are seen through the project’s entry sequence, refuge spaces, quiet spaces for staff as well as students, and dedicated storage and restroom facilities for staff members.

Sense of Community

Gathering spaces, pinup areas in public spaces, and visual connections to the exterior are some of the design strategies that support the principle of “Sense of Community.”

Beauty and Meaning

The project made use of design strategies that support the principle of “Beauty and Meaning” through key feature elements in the public areas, the strategic use of transparency between spaces, a unique flooring pattern, and by providing ample daylight and views to the exterior.

Dignity and Self Esteem

The principle of “Dignity and Self Esteem” is supported through spaces where staff or students can have private time to collect themselves, wall washing indirect lighting fixtures where there are mirrors and other reflective surfaces, and spaces where parents staff and students can all interact simultaneously.

Stress Management

Finally, Rise Early Learning makes use of design strategies that support the principle of “Stress Management” by providing key areas of heated flooring for students to rest, acoustic wall paneling for sound management, natural light for moderating mood.

What We Learned and Next Steps

In the grand scheme of things, research around trauma-informed design is still in its early stages. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to the application of these design principles within educational spaces, much less the built environment in general. However, as designers our decisions can play a significant role in alleviating and reducing trauma of those who occupy the buildings we design.

Cuningham’s next step is to build a clearinghouse of design strategies that can potentially reduce traumatic triggers, improve people’s ability to recover from high stress situations, and make the built environment a better place overall by establishing a shared conceptual frame of reference. It is our hope that others will make use of the trauma-informed design approaches detailed in this article and come together in dialogue around how to best leverage research and experience to engage our communities, shape design solutions, and arrive at better project outcomes.

References

[1] Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, "Appendix C Historical Account of Trauma," in Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services: Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57, Rockville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

[2] V. J. Felitti, R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards, M. P. Koss and J. S. Marks, "Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Cuases of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study," American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 245-258, 1998.

[3] National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, "About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html. [Accessed 31 August 2022].

[4] R. F. Anda, V. J. Felitti, D. J. Bremner, J. D. Walker, C. Whitfield, B. D. Perry, S. R. Dube and W. H. Giles, "The Enduring Effects of Abuse and Related Adverse Experiences in Childhood: A Convergence of Evidence from Neurobiology and Epidemiology," European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 256, no. 3, pp. 174-186, 2006.

[5] L. C. Houtepen, J. Heron, M. J. Suderman, A. Fraser, C. R. Chittleborough and L. D. Howe, "Associations of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Educational Attainment and Adolescent Health and the Role of Family and Socioeconomic Factors: A Prospective Cohort Study in the UK," PLOS Medicine, vol. 17, no. 3, 2020.

[6] M. Metzler, M. T. Merrick, J. Klevens, K. A. Ports and D. C. Ford, "Adverse Childhood Experiences and Life Opportunities: Shifting the Narrative," Children and Youth Services Review, vol. 72, pp. 141-149, 2017.

[7] R. F. Anda, V. I. Fleisher, V. J. Felitti, V. J. Edwards, C. L. Whitfield, S. R. Dube and D. F. Williamson, "Childhood Abuse, Household Dysfunction, and Indicators of Impaired Adult Worker Performance," The Permanente Journal, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 30-38, 2004.

[8] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, "SAMHSA's Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach," Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD, 2014.

[9] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "YRBSS Data & Documentation," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm. [Accessed 3 October 2022].

[10] R. Petrone and C. R. Stanton, "From Producing to Reducing Trauma: A Call for "Trauma-Informed" Research(ers) to Interrogate How Schools Harm Students," Educational Researcher, vol. 50, no. 8, pp. 537-545, 2021.

[11] J. Pabel and A. Ellis, "Trauma-Informed Design: Definitions and Strategies for Architectural Implementation," Design Resources for Homelessness, Tallahassee, FL, 2015.

[12] P. Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc: San Francisco, 2018.

[13] B. Channon, The Happy Design Toolkit: Architecture for Better Mental Wellbeing, London: RIBA, 2022.

[14] C. Latane, Schools That Heal: Design with Mental Health in Mind, Washington, DC: Island Press, 2021.

[15] S. Maslin, Desinging Mind-Friendly Environments: Architecture and Design for Everyone, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers An Hachette Company, 2021.

[16] K. Souers and P. Hall, Fostering Resilient Learners: Strategies for Creating a Trauma-Sensitive Classroom, Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2016.

[17] S. Wise, Design for Belonging: How to Build Inclusion and Collaboration in Your Communities, California | New York: Ten Speed Press, 2022.