Equity & Diversity

Equity & Diversity

Cuningham Group conducted a presentation series this year on Gender Equity and Diversity. Organized by a team of our employees, we discussed the factors that go into making a firm successful. Cuningham Group continuously strives to be a leader in equity and diversity, which we view as a main component of firm success. Throughout the sessions, employees were encouraged to participate in thought-provoking discussions and lend their perspectives on the firm’s efforts to improve equity and diversity.

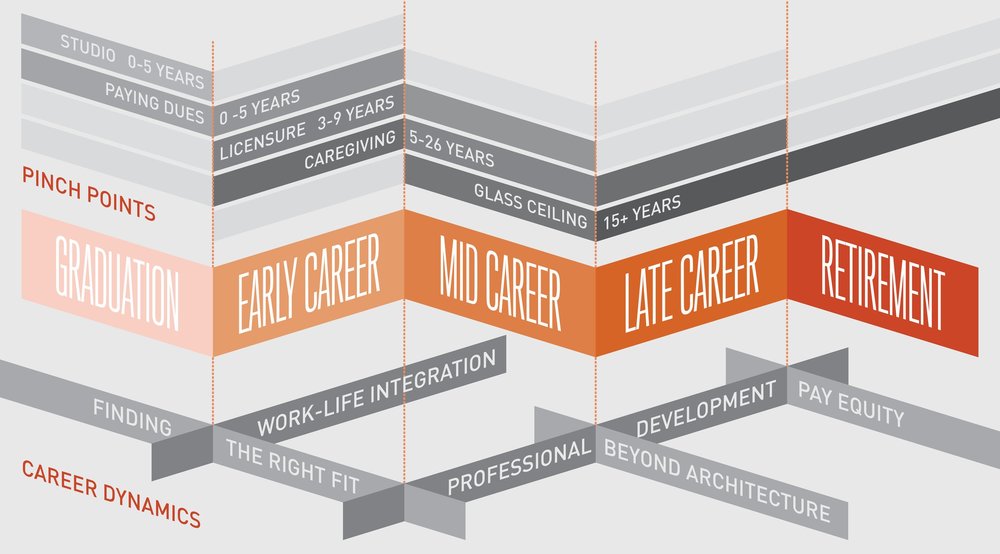

The group reviewed two 2016 AIA-based studies, which considered the experience of men, women and people of color in the architecture field. Using the survey results, AIA dissected various aspects of the field that architects found satisfying, inadequate or unequal in comparison to their counterparts. Here are some of the key findings:

2016 Equity in Architecture Survey

Courtesy of AIA Equity by Design

Courtesy of AIA Equity by Design

The AIA group began researching equity in architecture in 2014 with the goal of highlighting professionals’ career perspectives and the patterns that exist between their different viewpoints. The 2016 Equity in Architecture survey, conducted by AIA San Francisco’s Equity by Design group, provides a comprehensive analysis of the positions and career experiences of over 8,500 AIA members (both men and women) from all six inhabited continents.

Career Dynamics

[gallery link="file" size="medium" mkslideshow="true" type="slideshow" ids="19967,19968,19969,19971,19970"]

- Top three reasons for accepting a job: Quality of projects, opportunities for learning and firm reputation. These results were the same for both men and women.

- Metrics of success (positive perceptions of their current career): Categories that were viewed positively included autonomy, overall satisfaction, and confidence regardless of gender or race. Men tended to have more positive perceptions of their careers compared to women.

- Received career guidance: Men were more likely to seek out guidance from senior firm leaders compared to women.

- Pay equity: The average wage gap between men and women was larger in larger firms. Men make more money on average than women in every project role. Men who were design principals were paid a significantly higher salary than their female counterparts.

- Work-life balance: Women were more likely to report negatively on their work-life balance. Women were also slightly more likely to experience “burn out” in their jobs compared to their male counterparts.

Career Pinch Points

[gallery link="file" size="medium" ids="19975,19976,19977,19978,19979,19980"]

- Men and women agreed that their education helped prepare them for their careers, listing Design Thinking, Construction Methods and Graphic Representation as the most instrumental curricula for preparing them for their careers.

- Wages were comparable for those who gained their Master’s degree versus those who earned only their Bachelor’s degrees; however, men were still paid more than women.

- Professionals with fewer years of experience showed more diversity as opposed to those with more experience, meaning that diversity has the chance to grow with professionals that have under three years of experience.

2016 AIA Diversity in the Profession of Architecture

AIA published “Diversity in the Profession of Architecture,” a survey of more than 7,500 AIA participants that examines the impact of race, ethnicity and gender on the success of architecture firms. Results showed the following:

- Representation by gender and race: Women tended to agree that they are underrepresented in the workplace while men remained split on the issue. Overall, many participants agreed that people of color were underrepresented in the field.

- Challenges to career advancement: Women agreed that they were less likely to receive equal pay to men in a comparable position and believed that they were less likely to get promoted to senior positions.

- Work-life balance impact on representation of women: The identifying factor for the underrepresentation of women in the field was determined to be a result of the industry’s work-life balance. Among the factors included was the fact that women were not given significant opportunities when returning to the industry after leaving to start a family.

- Factors affecting the representation of minorities: Minorities found that several factors negatively affected their representation. These included: difficulty affording architecture school, lack of minority role models, the push towards getting a degree in a financially stable industry for financial security, as well as less exposure to architecture as a possible career option.

- Reasons for leaving the field: Most participants agreed that starting a family was an influential factor for architects leaving the field. Minorities also cited the fact that they were not being recognized and not being paid the same as their colleagues. Women participants tended to mainly list work-life balance as a reason for leaving the field. Men were more likely to leave the field in search of a more profitable profession.

- Job Satisfaction: Overall, the industry satisfaction was moderate, with women and minorities finding less satisfaction in the profession than their white, male counterparts.

The AIA survey responses suggest that to build more interest in the profession, the industry must increase their community outreach by supplying more knowledge to K-12 students, especially to minorities and young women. Younger students tend to develop an interest in architecture while finding their skills – math, science and drawing. Therefore, the industry must create a knowledge-base where students can understand the role of an architect as well as the proper steps to becoming one.

***Please note that not all survey findings from the 2016 AIA-based studies are presented in this article.