Inclusive Restrooms

Inclusive Restrooms

The design of public restrooms has long been a contested territory for civil rights issues and policy debates. The current gender-segregated restrooms common in educational facilities are coming under increased scrutiny by the LGBTQ community because they fail to recognize the non-binary nature of gender and create social difficulties for members of the transgender community. Although the issue is especially prevalent in K-12 schools, many school districts in the United States do not have the necessary information to actively address it.

Affecting Design

The push to move toward inclusive restrooms has implications on the architectural profession due to the fact that restrooms are heavily regulated by code. Although it was initially viewed as acceptable to have a minimum of at least one unisex restroom, advocates have come to view this number as insufficient. Additionally, these areas spatially regulate non-binary gendered people as “others.” As a result, the solution commonly advocated for today is extensive architectural intervention in developing multiple-occupant gender-neutral spaces.

There are several key design components that distinguish inclusive restrooms from their gender-segregated counterparts, including their look and feel. Key design differences include:

- Location, visibility and openness

- Full-height walls, doors and hardware

- Mechanical, electrical and plumbing

An inclusive restroom at St. Anthony Park Elementary School in St. Paul, Minnesota

An inclusive restroom at St. Anthony Park Elementary School in St. Paul, Minnesota

Code Implications of Restrooms in K-12 Facilities

While inclusive restrooms previously required building official approval as a satisfactory alternative design complying with the intent of the code, the 2018 ICC will allow single-user restrooms to fulfill the required fixtures count for facilities, without the sex designation. Once adopted, this impending change will allow for the inclusive restroom model to be accepted without going through the alternative design approval process. Additionally, the number of fixtures required will be equal to the number of fixtures currently required to be provided for each sex, but will not need to be segregated. This change in code will be international once adopted by all jurisdictions.

Size implications

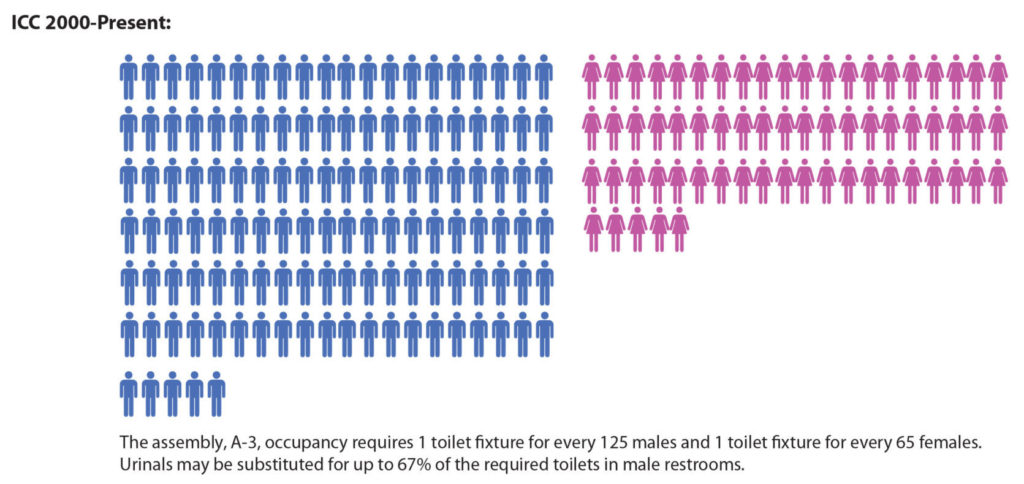

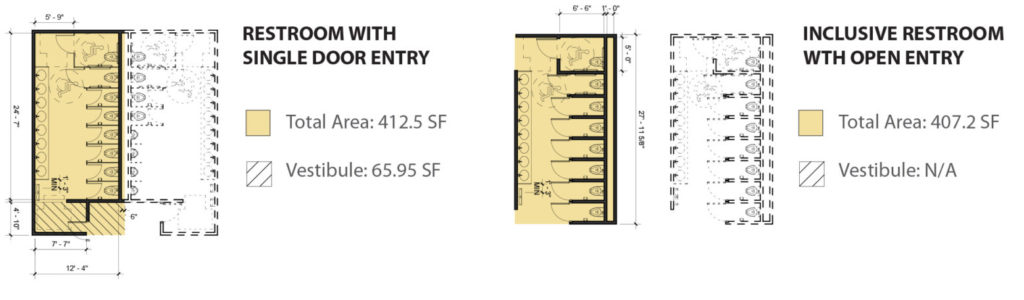

The research also found that inclusive facilities will affect space and building design for the better. Inclusive restrooms create space savings between 5-30 square feet per set of restrooms (see graphic below). Additionally, for jurisdictions like Minnesota that require a unisex restroom to be located adjacent each set of gender-segregated restrooms, space savings can be realized as all restrooms are considered unisex, eliminating the need for an additional restroom.

Inclusive facilities also save space due to fixtures. When calculating the required number of fixtures per code, architects traditionally divide the capacity in half, and then by the required number per code, to determine how many fixtures are required for each sex. Typically, this results in a non-round number of restrooms. Since it is impossible to build a fraction of a bathroom, architects have to round up for each sex. With the impending change in the code, the total capacity can be divided by the required number per code, which results in fewer bathrooms, less space, and less money to construct (see graphic).

Conclusion

There are several key design components that separate inclusive from gender-segregated restrooms, including location within school facilities, visibility, openness to the hallway, full-height walls and doors, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems. All of these design components translate into a cost-premium for this facility model. However, the flexibility this model affords in terms of location and square footage savings, not to mention the reduced stress afforded to individuals on the gender spectrum, counterbalances this increased cost. Ultimately, Cuningham believes that inclusive restrooms will become a significant component in the future of educational facility designs.

Heidi Neumueller, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP

Heidi brings architectural experience in programming and long-range planning to Cuningham . She is a licensed architect in the state of Minnesota. In addition to being a member of the American Institute of Architects and a LEED Accredited Professional, Heidi was also a member of the 2012 Council of Educational Facility Planners International (CEFPI) Board of Directors in Minnesota.